One of the most surprising things I learned as a new manager was that people actually don’t give each other that much critical feedback. Even if there is something that has been pissing them off for months, maybe years: Most people will not pull the other person aside, tell them what bothers them, and suggest to do something differently.

Instead, one of three things usually happens.

One, people might simply say nothing at all and let their frustration grow. This causes more damage over time.

Two, things come up months later in an annual peer-to-peer review — which makes them little actionable for the receiver, because they cannot connect the feedback to a concrete situation. It’s just too long ago.

Three, people complain to their manager during a one-on-one — which might put the manager in an uncomfortable “he said, she said” situation, and consume a lot of their time and energy.

None of these three options is ideal, because they don’t tackle the root of the problem, or only try to do so indirectly. Instead, wouldn’t it be nice if people “simply” told each other, in a constructive way, when they are annoyed or disappointed by something the other person did?

Straight talk

I am blessed with some remarkable colleagues, and this is exactly what happened to me a couple of days ago.

We had intended to gather data on a test we were running, but somehow, the data did not arrive. My colleague, Tobias, tried to find out why the data was not coming in. For days, he examined the test setup, logged in to remote machines, ran tests himself, and double-checked everything.

No success.

In the end, seven days after we started, he and another colleague noticed by chance that one of the tests that everybody thought was activated, was in fact not activated. And the person who had activated the wrong combination of tests was — me.

Tobias then did something that, in hindsight, I highly appreciate.

He gave me the straight talk.

First, he explained to me how much extra work this mistake had caused him. Then, he asked how we can avoid something like this in the future. Because, of course, mistakes will always happen. However, what he was missing was some more ownership on my side to push for an investigation result, and to coordinate the efforts better. After all, I was primarily responsible for the outcome of the test.

Together, we revisited the events that had happened before and after the mistake, and identified where I should have been more thorough in following through. It became clear to me that Tobias was right.

I benefit from this interaction. Through Tobias’ willingness to give critical feedback to a peer, I learned a valuable lesson. Maybe I would have learned something from the mistake anyway, but it was only through our conversation that it was really driven home.

Tobias, also, benefits from the interaction. From now on, I will work towards higher standards, and our collaboration will be a little smoother. Moreover, my respect for him has grown.

Finally, our team leads benefit from the interaction — because they did not have to spend time and energy on this issue. The matter was resolved purely between us, without any escalation. In fact, they don’t even know about it (unless they read this blog post).

Obstacles

So, if critical feedback among peers can have such positive effects, why is it not given more often?

In Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni tells about the journey of a team of executives who, guided by their new CEO, examine how they work together.

When the topic comes to a lack of constructive conflict on the team, one of the executives brings up the most obvious aspect of the equation:

“I hate this one. I just don’t want to have to tell someone that their standards are too low. I’d rather just tolerate it and avoid the…“

When he hesitates, trying to find the right words, a team mate finishes the sentence for him: “…the interpersonal discomfort”. Interpersonal discomfort is certainly part of the reason why critical feedback is not given more often in general.

However, when it comes to critical feedback among peers — be it on the C-Level or not —, there is yet something else. Another character in the book puts it this way:

“…we’re supposed to be equals. And who am I to tell Martin how to do his job, or Mikey, or Jan? It feels like I’m sticking my nose into their business when I do.”

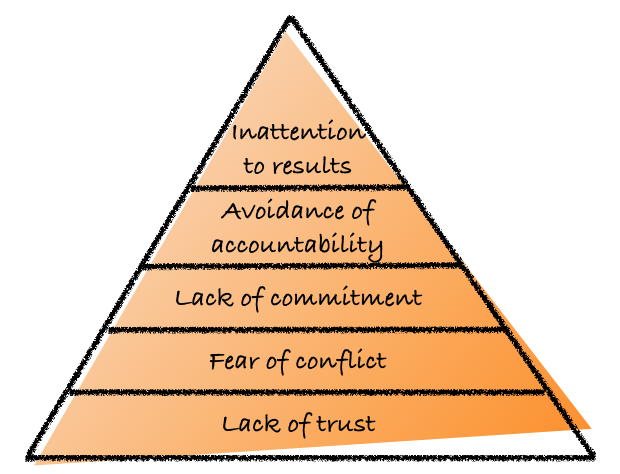

In other words, we don’t want to give the impression of feeling superior to our peers. In order to show how this common and understandable reluctance can be overcome, the new CEO introduces a model of dysfunctions that looks like this (read from bottom to top):

In short, a lack of trust on the team leads to fear of open and constructive conflict. If I don’t trust my team mates, then it might be too risky to disagree with somebody, because I don’t know how they will react. Maybe, they will counter-attack.

The result is artificial harmony, where issues are not addressed and everybody seemingly gets along. If issues are not addressed, I will not be able to voice my true opinion and concerns about the group’s plans or decisions. This, in turn, leads to a lack of commitment and buy-in: I will not fully stand behind a plan when my input was not heard.

If I have no buy-in, then nobody can really hold me accountable (“Lack of accountability”), because I can always respond: “Well, I never really agreed to that plan, anyway.” This avoidance of accountability for team goals lets me focus on my individual goals and put them first. Team results will suffer as a consequence, and nobody cares too much (“Inattention to results”).

Avoiding the dysfunctions

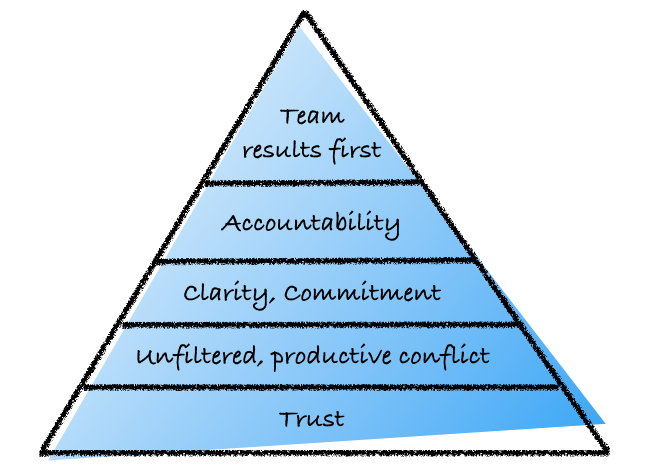

However, when reversed, the model of the five dysfunctions also gives us guidance on how to avoid them. Again starting from the bottom of the pyramid, trust on the team allows people to feel safe to engage in critical discussions.

Tobias trusted me to remember that he had good intentions. He knew that I knew that he did not mean to attack me. So, he used this trust to start a critical discussion.

In the long run, critical discussions are vital for any organization or group of persons that wants to grow and develop — for any team, any department, any couple, any family, and any company.

In critical discussions, competing opinions are voiced. People choose their words based on what they really think — not based on how they want others to react. When there is something truly bothering or concerning them, they need somebody to hear it.

Surprisingly, to most people, knowing that they have been heard is more important than getting their way. The end result of the discussion might not be what they initially had in mind, but if they know they have been heard, they will support the end result anyway — as long as there is a clear and unambiguous decision.

And with that, we have reached the third layer of the pyramid: A clear and unambiguous decision makes true commitment possible. With a clear goal, the team can measure themselves in terms of this goal. Peer accountability becomes possible.

It becomes possible to say: “Hey Sarah, we all said we would extract common functionality more to bring down code size. In this pull request, you copy a lot of code from another module. Can you please have another look before we merge this?”

Or, “Matt, you agreed to making the move to the new infrastructure last week, and it’s still not done. We are slipping behind schedule. What happened?”

Or, “Tom, the communication for this should have been out yesterday, and it’s still not out. Is something blocking you?”

In a well-functioning team, there is nothing more motivating than the fear of letting your team mates down. Clear decisions and goals make it visible when that is the case. If you are a team lead, this is where you want your team to be.

Everybody is aware of the team goals.

Everybody was involved in agreeing to them.

Everybody cares about reaching them.

In such an environment, nobody entertains lasting bitter feelings about being held accountable. On the contrary, even: When somebody asks you to do a better job, you can take it as a compliment, because the other person is saying: “Hey, you’re not up to your usual standards here. I know there is a better version of this work still brewing inside of you. Let it out! I know you can do it!”

So, next time somebody asks you to do a better job, maybe you want to thank them for it.

I'm Tom Bartel, Germany-based software developer, engineering manager, speaker, and human communication geek. More

I'm Tom Bartel, Germany-based software developer, engineering manager, speaker, and human communication geek. More